- Home

- Grant Fuhr

Grant Fuhr

Grant Fuhr Read online

PUBLISHED BY RANDOM HOUSE CANADA

Copyright © 2014 Grant Fuhr

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2014 by Random House Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, a Penguin Random House Company. Distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.randomhouse.ca

Random House Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Fuhr, Grant, 1962–, author

Grant Fuhr : the story of a hockey legend / Grant Fuhr with Bruce Dowbiggen.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-307-36281-0

eBook ISBN 978-0-307-36283-4

1. Fuhr, Grant, 1962–. 2. Hockey goalkeepers—Canada—Biography. 3. Hockey players—Canada—Biography. 4. Black Canadian hockey players—Biography. I. Dowbiggin, Bruce, author II. Title.

GV848.5.F87A3 2014 796.962092 C2014-902984-5

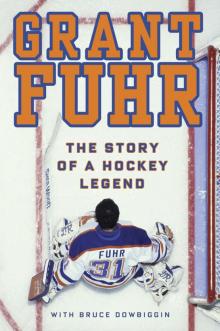

Cover image: © David E. Klutho / Sports Illustrated / Getty Images

Interior goalie silhouette: © Daniel Schweinert / Shutterstock.com

v3.1

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword

Introduction NOVEMBER 3, 2003

HOCKEY HALL OF FAME

GAME 1 OCTOBER 14, 1981

WINNIPEG 4 EDMONTON 2

GAME 2 JANUARY 9, 1983

DETROIT 4 EDMONTON 3

GAME 3 MAY 10, 1984

EDMONTON 1 NEW YORK ISLANDERS 0

GAME 4 APRIL 9, 1986

EDMONTON 7 VANCOUVER 3

GAME 5 SEPTEMBER 13, 1987

CANADA 6 USSR 5

GAME 6 APRIL 15, 1989

LOS ANGELES 6 EDMONTON 3

GAME 7 FEBRUARY 18, 1991

EDMONTON 4 NEW JERSEY 0

GAME 8 APRIL 20, 1993

BUFFALO 4 BOSTON 0

GAME 9 APRIL 18, 1996

ST. LOUIS 4 TORONTO 5 OT

GAME 10 MAY 4, 1999

ST. LOUIS 1 PHOENIX 0

EXTRO OCTOBER 9, 2003

EDMONTON 5 SAN JOSE 2

Photo Insert

Acknowledgments

Selected References

About the Authors

FOREWORD

Around 2001, my family had new neighbours living on our street in the Signal Hill area of Calgary. They were from Texas, and everything about winter was a revelation for them. The snow. The cold. The clothing. At the time they loved it. They also loved the quiet family across the street. “They’re so nice,” Colleen Moreland would say in her Texas drawl. “I’m not sure what he does, but he seems like a very nice man. Quiet but nice.”

The quiet man she referred to just happened to be one of the greatest hockey goalies ever, Grant Fuhr. No Canadian could have missed the face, but my neighbour was blissfully unaware. I told her, imagine living across the street in Texas from Roger Clemens or Tony Dorsett. That’s the status of Grant Fuhr in Canada’s hockey hierarchy. Plus, he was the first black star in the game. Almost everywhere he goes in Canada he is immediately recognized by fans. She smiled apologetically and said, “I didn’t know that. That’s wonderful.”

Grant was wonderful on the ice, but the unsuspecting acceptance of a neighbour was more comfortable for a man who preferred to be judged on his play rather than the colour of his skin or the friends he kept. Grant had pursued hockey, and he got fame in return. It was not always a great bargain living his life in the eye of the media and fans. In retirement, Grant prefers the quiet of the golf course to the throngs of people who want to shake his hand. Like his parents, he’s unimpressed with fame for its own sake, and now prefers the anonymity of his current life and family. He’s earned that comfort. He sees his life as a learning example for his four kids and for others who follow his exploits. It’s an amazing tale of an adopted child of mixed race who emerged from a small town in northern Alberta to become a household name in Canada and around the hockey world. The saga of a star who conquered hockey and his own problems with honesty and a self-effacing smile. If you told people how it happened they wouldn’t believe you.

Here is the plain truth.

INTRODUCTION

NOVEMBER 3, 2003

HOCKEY HALL OF FAME

On one glorious night, Toronto played host to a meeting of hockey royalty from the days of the NHL’s last great dynasty—the Edmonton Oilers of 1984–90. Stars such as Wayne Gretzky, Kevin Lowe, Glen Sather and Paul Coffey filled the Great Hall of the Hockey Hall of Fame, while many teammates from the day were watching via the television broadcast. Coffey, the celebrated defenceman, sat just a few rows away from the podium where his former goalie Grant Fuhr now stood nervously in a tuxedo. One observer joked that this seat was probably closer than Coffey ever got to Fuhr on the ice during his legendary days rushing up to the other zone with the Edmonton Oilers. Like the best jokes, the jibe about the freewheeling Coffey had just enough truth to drive home the point. In his days as the Oilers’ goalie, Grant was often a solo act, left to defend the home net while his prolific teammates swarmed the opposing end in search of goals, goals and more goals. The isolation—this abandonment by teammates—might have broken many other goalies. It’s not hyperbole to say, as Ken Dryden once did, that goaltending is “grim, humorless, largely uncreative, getting little physical pleasure in return.”

But Grant Fuhr never took it personally. With a characteristic shrug of the shoulders he’d just handle the opposing shooters all by himself. And on most nights during Edmonton’s run of five Stanley Cups in seven years that’s exactly what happened. No muss, no fuss. “It was well within his right to stand up and say, ‘Come on guys, we’re giving up five, six, seven breakaways per game,’ ” says teammate Marty McSorley. “He had every right to stand up in the dressing room and go, “C’mon guys,’ but he never did. Not a peep of complaint.”

For 17 NHL seasons, Grant defied the odds. And now, on this day, the Hall of Fame beckoned. As he nervously looked out over the assembled crowd to deliver his induction acceptance speech, the audience might have been forgiven for wondering where Fuhr might start. There was, after all, no easy way to sum him up, to describe his career. No. 31 was the culmination of the many streams flowing through his life and career. Starting out as an 18-day-old adoptee of mixed race in Spruce Grove, Alberta, with the most challenging of prospects, Fuhr authored a remarkable story of talent, resilience and a comeback from personal demons that almost ruined him and his career. Overcoming injuries in his mid-30s, he produced a triumphant second act in St. Louis long after the hockey “experts” thought he was finished.

Perhaps not surprisingly, he started his talk with the pioneer. The first superstar of colour in the NHL, Fuhr was a low-key model for racial equality in hockey, a worthy successor to pioneer Willie O’Ree, who broke the NHL’s colour barrier in 1958. “I’d like to thank Willie O’Ree,” Grant announced as O’Ree himself looked on from the crowd. “It’s an extra-special honour to be the first man of colour in the Hockey Hall of Fame. It just shows that hockey is such a diverse sport that anyone can be successful in it. I’m proud of that, and I thank Willie for that.”

To most of those gathered in the Great Hall, Grant was synonymous with the Oilers dynasty. It was hard to separate the kid who’d grown up in the Edmonton bedroom community of Spruce Grove from the city and that wonderful team. “I see Paul here, Wayne, Kevin [Lowe] … we had a huge family. It was all a team. More t

han a team it was a family. That said the most of it, and that’s why we were successful.”

Grant thanked one of the earliest Oilers for helping to launch his story. Ron Low took a teenaged goalie prospect fresh from the Victoria Cougars and taught him about life in the NHL. “He was my partner in my first year and a big part of where I am. For an 18-year-old goalie it takes a lot to get comfortable in the NHL, and Ronnie was a huge part of that. He was instrumental in that.”

Grant also recalled two “special” relationships: one with the man who’d drafted him into the NHL, Oilers coach and general manager Glen Sather, and one with former Oilers and Buffalo Sabres coach John Muckler. “Glen and I probably had a little more special relationship than most coaches would want. I seemed to find a lot of time in his office. Some good, some bad. John Muckler, I seemed to spend a lot of time in that office too.”

Mike Keenan, Grant’s coach with Team Canada in the 1987 Canada Cup, revived the goalie’s career late in his playing days, in St. Louis. “Lot of things have been said about him,” Grant noted about Keenan. “His style’s a little bit different, but he gave me a fabulous opportunity. It was a time in my career where you’re thinking about quitting, and he gave me that opportunity to play. And I played a lot. He let me play every night. As a goalie that’s what you want: the opportunity to play every night. And he gave me that.”

It was also in St. Louis that Grant’s unique approach to conditioning was changed for good by legendary Olympic coach Bobby Kersee. “At one point I thought I was a good athlete,” Fuhr said. “I was athletically good, but not a good athlete. Through Bobby, I found out what it was like to be a good athlete. I know Glen had pushed me to do that. Muck and I had a few conversations over that. I spent a lot of time riding a bike in Buffalo with one of our assistant coaches, John Tortorella. I might have been the only guy who rode every day and gained two pounds while the coach lost eight.”

Finally, when conditioning was not enough, Grant’s knees and shoulders were repaired by team doctors—extending his career to a remarkable 17 years at the top of the world’s greatest hockey league. “They played a special part in my career,” he said. “I spent a lot of time being put back together again. This body seems to have broken down a few times, and got written off a few times. But the doctors put me back together again.”

Looking into the crowd, Grant could see his longtime friends and his four children, including son Robert (RJ)—wearing a suit for one of the few times in his life. “Kendyl, Rochelle, son RJ, daughter Janine: they make the big sacrifice. You get traded; you don’t see the packing, you don’t see the moving. Somehow it happens. We don’t see that; we’re pretty much married to the game of hockey. First and foremost, that’s probably our wife—the game of hockey—and they take a back seat to that. I thank them for that.

“My friends have been there through thick and thin. I’ve had a different road than most people to get here. Most of it good, some not so good. A little bumpy along the way. But they’ve always been there. You have to have that love and support.

“In closing, it’s the greatest game in the world, I’m happy to be part of it and I’m more happy to get back to it. It’s special. Thank you.”

To understand just how special requires a voyage through the singular games and moments of a remarkable life lived in full view.

GAME 1

OCTOBER 14, 1981

WINNIPEG 4 EDMONTON 2

Sports fans can be forgiven for failing to note the NHL debut of a wiry 19-year-old named Grant Fuhr against the Winnipeg Jets in the fourth game of the Edmonton Oilers’ 1981–82 season. That same autumn day, Ray Burris of the Montreal Expos had out-duelled Fernando Valenzuela of the Los Angeles Dodgers 3–1 at Dodger Stadium—the first-ever League Championship Series win for a Canadian Major League Baseball team. Edmonton sports fans were also buzzing over the hometown Eskimos after their 24–6 win over the Ottawa Rough Riders pushed the defending Grey Cup champs to a 12–1–1 record in the Canadian Football League. In the NFL, Lawrence Taylor of the New York Giants was terrorizing quarterbacks just a month into his rookie season.

These were still the days before every game in a team’s schedule was broadcast, before all-sports TV networks blanketed the medium with Top-10 lists and highlights from across the continent. What attention Grant’s debut garnered came only from the local print and TV newscasts. No wonder there was less than a full house that night at Northlands Coliseum for what, in the end, would be an historic debut.

Besides, who was this junior kid, anyhow? Wasn’t Andy Moog, the hero of the Oilers’ dramatic sweep over Montreal in the 1981 playoffs, still the starter? Sure, Moog had stumbled, surrendering 10 goals while splitting his first two starts of the season. And Ron Low, on hand to be the reliable backup, had won 7–4 over the Los Angeles Kings just four nights before. There’s that old expression—the one that says if an NHL team has two starting goalies then they’ve got none. And now the Oilers had three netminders? NHL teams can’t carry three goalies: what was Oilers general manager (and coach) Glen “Slats” Sather thinking? Okay, maybe the Jets were a weak sister—brought in with the Oilers from the World Hockey Association and dead last at the end of the 1980–81 season—but this was no time for experimenting, not after the Oilers had proved themselves playoff worthy earlier in the year. Right?

If it was any consolation to the baffled 17,430 in attendance at Northlands Coliseum, Fuhr himself hadn’t expected to be standing between the pipes against the Jets either. As he gazed down the ice at Winnipeg’s rookie phenom, Dale Hawerchuk, his nemesis from the previous spring’s Memorial Cup in the CHL, Grant had to be wondering what a teenager from Spruce Grove was suddenly doing in the uniform of his home team.

Grant:

I never even thought that I could stay in Edmonton my first year, because with Andy, the Oilers had won. The city was in love with him. Andy had played unbelievably against Montreal, and in those days it was unusual that they should beat Montreal, with Guy Lafleur and Larry Robinson and Serge Savard. We’ve also got Ronny Low there at the time and Gary Edwards. There were four or five guys that had NHL experience, besides Andy. I never even thought about making it the first camp. You keep waiting and waiting, thinking okay … you’re watching all these other guys getting sent back down to the junior team—getting sent home. You figure at some point, you’re going to get that call. So then I get the call up to the office and I go, “Okay. This must be it.” When I get there Slats looks at me and says, “I think you should find a place to live here in Edmonton.” The call never came.

All rookies experience some form of terror or nerves in their initial NHL game. But this first start was uncharted territory. Before Grant’s introduction to the NHL, just a handful of teenagers had donned the goalie pads in a league game before their 20th birthday. Player shortages during the Second World War had led the Detroit Red Wings to call up Harry Lumley (by no coincidence nicknamed “Apple Cheeks”) at the tender age of 17. But Lumley was an exception in a time where there were just six starting jobs in the NHL, all of them dominated by veterans like Terry Sawchuk, Johnny Bower and Gump Worsley. And lack of opportunity wasn’t the only factor working against teenaged hopefuls. When the NHL amateur draft was universalized in 1969, players weren’t even eligible until the year of their 20th birthday. It wasn’t until the World Hockey Association emerged in 1972 that teenaged players again got a chance to play in the pros. By 1981, 18- and 19-year-olds were finally eligible to play in the NHL, after threats of court challenges forced the league to match the WHA rules on eligibility. A few years earlier, Grant would have been looking at two more years of junior-level play, waiting impatiently for his chance to suit up with the big guys. Instead, he found himself starting for the Edmonton Oilers at the age of 19 years, 16 days.

But as Wayne Gretzky got set to take the opening faceoff for the Oilers that fine fall evening, Grant’s youth took a backseat to something else that set the young goalie apart: he was the first black goalie t

o start an NHL game in the league’s 64-year history.

In 1962, Bob and Betty Fuhr had reluctantly given up on the idea of having children themselves, and put their names in with various Alberta government agencies, signalling their desire to adopt. In the days before in-vitro fertilization and surrogate parenting, this was the common way to have a family when nature denied you one. For better or worse, there were still ample lists of children for adoption in that era, and in the Canada before cultural diversity, families wishing to adopt a child of their same culture or religion had a reasonable hope of doing so. Trans-racial adoptions were almost non-existent in North America until the 1950s, as experts believed children should grow up in their own racial environment. By the 1960s, however, the practice had become more accepted, though there was still apprehension, especially outside of major urban areas. Bob Fuhr, an insurance salesman, and Betty, a housewife, had decided that it might be best if they didn’t choose a mixed-race child. How could they honour their child’s heritage without knowing anything about it? Would the child grow up to be lost in their white culture, adrift from his or her roots?

It was with this trepidation that Betty looked at the 18-day-old baby brought to her door by adoption officials. The child, said the official, had the Metis mark, a dark birthmark at the base of the spine that was thought to signify a child of mixed Native and white parentage. Betty understood what she was being asked to accept. “Trans-racially adopted children do not have the advantage of learning about their birth culture through everyday cues and bits of knowledge, assimilated almost unconsciously over years, as in single-race families,” writes Jana Wolff, author of Secret Thoughts of an Adoptive Mother and the parent of a biracial child. “So the responsibility that parents have to their different-race children can seem overwhelming.” It must have seemed that way for Betty, too. But whatever her fears, they were quickly overcome as she looked at the baby boy in the blankets. “The love was there,” Betty later told Sports Illustrated. “It came to me.”

Grant Fuhr

Grant Fuhr